Post by Goldilocks on Apr 22, 2018 18:02:59 GMT

Here are an article on The HPA axis, which is related to cortisol and stress, in relation to attachment issues:

www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=11&ved=0ahUKEwibzNP3tc7aAhVDZ1AKHf0XCaM4ChAWCCcwAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.socialpsychology.org%2Fdownload%2F9161%2FPietromonacoDeBusePowersCDPSinpress.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1UjdDmDKH__xYxOzad1jMx

What features of relationships potentially influenceemotional and physical health?

Is it the mere presence or absence of close bonds with others, the

objectively positive or negative qualities of those bonds, or people’s perceptions of and

expectations about them that matter? Recent work on the physiological correlates of attachment

processes in adult romantic relationships has begun to provide some answers regarding the latter.

Through past relationship experiences, people develop distinct lenses through which they

interpret events in their current romantic relationships. These different lenses, or attachment

styles, are inextricably connected to people’s affective responses to relationship stressors,

including physiological reactions to stressors, and their ability to regulate distress.

Most evidence connecting attachment styles to affective reactions comes from studies

examining people’s self-reported, consciously accessible affective experiences, but affective

reactions occur at multiple levels, including at a less consciously accessible physiological level.

Links between attachment and physiological indicators of affective reactions are important to

consider because they are distinct from self-reports of distress (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004;

Powers, Pietromonaco, Gunlicks, & Sayer, 2006), and because they offer likely pathways

through which attachment-related processes may influence later health and disease outcomes.

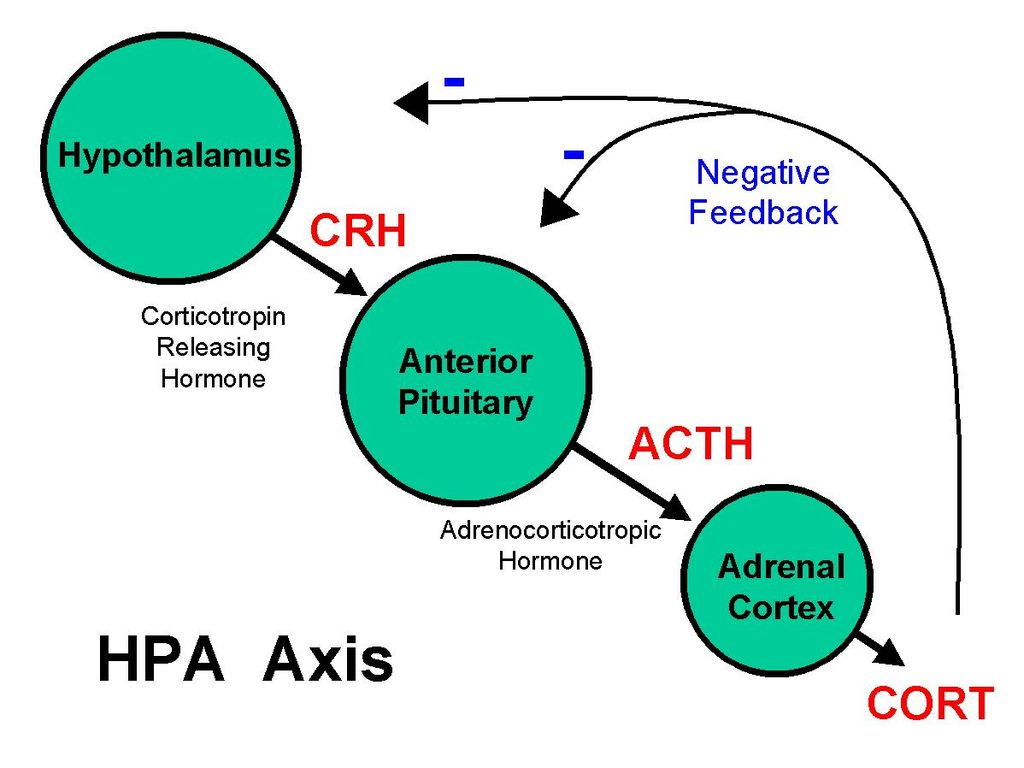

In this article, we focus on how attachment styles are connected to physiological stress

responses that reflect activation in the HPA axis, which is a major stress response system in humans modulating the release of cortisol.

Although other physiological systems (e.g., thesympathetic adrenal medullary axis) are implicated in stress responses (e.g., cardiovascular

activity), we focus specifically on HPA responses because a large literature has identified HPA

responses as a mechanism through which psychological stress may influence a wide range of

mental and physical health outcomes (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007).

This article reviews research suggesting that HPA responses may offer a pathway through which

attachment in adult relationships shapes health and disease outcomes. We first provide a brief

overview of attachment theory in connection to affect regulation and then discuss evidence

demonstrating that attachment styles predict different patterns of cortisol stress responses,

especially in attachment-relevant contexts.

Is it the mere presence or absence of close bonds with others, the

objectively positive or negative qualities of those bonds, or people’s perceptions of and

expectations about them that matter? Recent work on the physiological correlates of attachment

processes in adult romantic relationships has begun to provide some answers regarding the latter.

Through past relationship experiences, people develop distinct lenses through which they

interpret events in their current romantic relationships. These different lenses, or attachment

styles, are inextricably connected to people’s affective responses to relationship stressors,

including physiological reactions to stressors, and their ability to regulate distress.

Most evidence connecting attachment styles to affective reactions comes from studies

examining people’s self-reported, consciously accessible affective experiences, but affective

reactions occur at multiple levels, including at a less consciously accessible physiological level.

Links between attachment and physiological indicators of affective reactions are important to

consider because they are distinct from self-reports of distress (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004;

Powers, Pietromonaco, Gunlicks, & Sayer, 2006), and because they offer likely pathways

through which attachment-related processes may influence later health and disease outcomes.

In this article, we focus on how attachment styles are connected to physiological stress

responses that reflect activation in the HPA axis, which is a major stress response system in humans modulating the release of cortisol.

Although other physiological systems (e.g., thesympathetic adrenal medullary axis) are implicated in stress responses (e.g., cardiovascular

activity), we focus specifically on HPA responses because a large literature has identified HPA

responses as a mechanism through which psychological stress may influence a wide range of

mental and physical health outcomes (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007).

This article reviews research suggesting that HPA responses may offer a pathway through which

attachment in adult relationships shapes health and disease outcomes. We first provide a brief

overview of attachment theory in connection to affect regulation and then discuss evidence

demonstrating that attachment styles predict different patterns of cortisol stress responses,

especially in attachment-relevant contexts.

In one study, participants believed their

partner would be interviewed by an attractive opposite-sex experimenter about the intimate

details of the partner’s past and current romantic relationships and that they and their partner

would later watch a video of the interview (Dewitte, De Houwer, Goubert, & Buysse, 2010). In

this situation, greater cortisol reactivity was observed for men who were more anxiously attached

and for women who were higher in both attachment anxiety and avoidance (i.e., reflecting

“fearful-avoidance,” or a desire for closeness while fearing rejection).

partner would be interviewed by an attractive opposite-sex experimenter about the intimate

details of the partner’s past and current romantic relationships and that they and their partner

would later watch a video of the interview (Dewitte, De Houwer, Goubert, & Buysse, 2010). In

this situation, greater cortisol reactivity was observed for men who were more anxiously attached

and for women who were higher in both attachment anxiety and avoidance (i.e., reflecting

“fearful-avoidance,” or a desire for closeness while fearing rejection).

For example,

avoidantly attached married individuals showed an increased inflammatory response (IL-6) after

a conflict interaction with their spouse but not after a support interaction (Gouin et al., 2009).

avoidantly attached married individuals showed an increased inflammatory response (IL-6) after

a conflict interaction with their spouse but not after a support interaction (Gouin et al., 2009).